Down the ECS Rabbit Hole

My unquenchable desire to refactor everything before it even begins kicked in. This post is part of an ongoing series about Flying is Hard.In my last log I mentioned that I get bored of projects really easily. My computer is literally a graveyard of probably 15 or so prototypes in various forms of completion (maybe 75% of which are platformers) that don't get any love. Many of which include a different design pattern from the rest, in keeping with my tradition of "try all the design patterns!" Well, I had told myself I wasn't going to go down that road again but after seeing a GDC talk about ECS I was itching with intrigue and just HAD to try to implement it.

Since this is a Unity project (eagle-eyed readers may have noticed that the first prototype video I shared was SpriteKit tho!), when it comes to ECS the current go-to framework is Entitas-CSharp which is a ECS framework made specifically for C# / Unity by some of the guys at Wooga. It's some really interesting tech, that said after doing some tests and playing around with it I decided that it just wasn't for me. It felt too detached from the normal Unity workflow and I didn't like how certain things were handled as well as the fact that it mostly depends on generated code; it just felt like too much was out of my hands and controlled by some black box.

I spent the next few weeks playing around with writing my own ECS framework with varying levels in intricacy; but after about 4 different versions I decided to settle on an extremely simplified version of the pattern that could potentially be considered an ECS/MVC pattern. It enforces the separation of data / logic but maintains the standard Unity workflow and keeps how things are working very transparent for easy debugging.

Brief overview of the pattern I settled on

The pattern I wound up going with enforces the following structure:

- Entities are MonoBehaviours and each GameObject should be limited to 1 Entity

- Components are public and serializable, and make up the public API for Entities

- Systems are private and take in a selection of Components that are then used for Entity manipulation

- Entities act as delegates for systems for the built-in Unity MonoBehaviour messages

This allows for quick addition of new features, easy debugging of functionality ("oh, the thrust is acting up? let me pop into the thrust system and see what is going on"), performance benefits due to limiting each GameObject to only one MonoBehaviour, and the standard Unity workflow of throwing GameObjects into a scene and being able to tweak everything needed in there with no issues. Since I am currently not dealing with any entity managers, implementation/scaffolding was very trivial as well since it just required writing base classes for Entities, Components, and Systems.

High-level examples

Let's start with entities since they hold everything together and will perhaps give you a better idea of where the other two fit in.

// ExampleEntity.cs

using FlyingIsHard.Assets.Bengsfort.Components;

using FlyingIsHard.Assets.Bengsfort.Systems;

using FlyingIsHard.Assets.Bengsfort.Entities.Core;

namespace FlyingIsHard.Assets.Bengsfort.Entities

{

// BaseEntity inherits from MonoBehaviour so it can delegate Unity messages

public class ExampleEntity : BaseEntity

{

// All components are serializable, so this will be editable within Unity

public ExampleComponent component;

// Systems are handled per-entity currently

private ExampleSystem m_System;

// Instantiate a new system instance, passing the component to it

void Start()

{

m_System = new ExampleSystem(component);

}

// Run the systems tick every frame if it is active

void Update()

{

if (m_System.active)

m_System.Tick();

}

}

}As I mentioned before, Entities just hold all of your components and act as a delegate for Unity events and systems. All of the components are serializable, so each one can be fully configurable within the Unity editor and tweaked during the play state to test values at runtime. Let's take a look at a component now:

// ExampleComponent.cs

using System;

using FlyingIsHard.Assets.Bengsfort.Components.Core;

namespace FlyingIsHard.Assets.Bengsfort.Components

{

[Serializable]

public class ExampleComponent : BaseComponent

{

public double score = 0;

public double scoreStep = 2;

public Text text;

public string label

{

get

{

return score + " points";

}

}

}

}This is an example of a somewhat typical component, with the addition of a getter member to demonstrate that the only logic allowed are formatting helpers or similar. They are small and focused on maintaining the state of a particular functionality. This is also very nice because it means that I can rebuild an object at any point completely just by tossing the proper state into it. Now lets look at the systems that actually use these states.

// ExampleSystem.cs

using FlyingIsHard.Assets.Bengsfort.Components;

using FlyingIsHard.Assets.Bengsfort.Systems.Core;

namespace FlyingIsHard.Assets.Bengsfort.Systems

{

public class ExampleSystem : BaseSystem

{

ExampleComponent m_State;

ExamplePlayerComponent m_Player;

// Increase the score every frame

public override void Tick()

{

// Early out if we shouldn't increment the score

if (!m_Player.incrementScore)

return;

var step = m_State.scoreStep;

if (m_Player.inBonusZone)

step *= 2.0; // Double points in the bonus zone

m_State.score += step;

m_State.text = m_State.label;

}

// Cache the state references on instantiation

public ExampleSystem(ExampleComponent component)

{

m_State = component;

// Example static component

m_Player = StageManager.Player.playerState;

}

}

}As you can see above, the systems are basically pure logic focused on a single job. They cache state/data references on instantiation and then manipulate those as needed to get their job done.

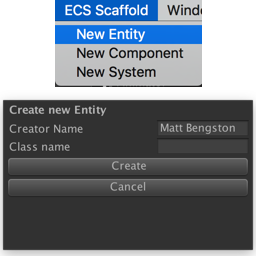

One thing with this pattern though is that you wind up creating a lot of files very quickly. In most instances for example every time you make an entity you can also expect to make a component and system to go along with it, at least when implementing a new feature. To speed this up I wound up making an editor script that adds a new window menu to Unity for fast creation of entities, components and system files:

As I've been getting much more proficient with making editor scripts lately, this turned out to be pretty easy to implement. The EditorWindow docs are great for figuring out how to create a custom window, so all I had to focus on was the file generator portion of the functionality. The route I went to make that happen was a pretty basic one:

- Have template C# files for each type of class

- On press of the create button, find the correct template file and read all of its contents into a string

- Use

String.Formatto inject the values from the editor window text fields into the template - Write the file to disk and force Unity to import the new C# file

Outside of the normal editor window boilerplate stuff, all of this was able to fit into the nice little method below.

void CreateClassFromTemplate()

{

// Get the template path

var tmplPathPrefix = Application.dataPath + "/Bengsfort/Editor/Scaffolding/Templates";

var tmplFile = (tmplPathPrefix + "/" + m_DialogTitles[(int)type] + "Template.cs.tmpl")

.Replace('/', Path.DirectorySeparatorChar);

// Check for the existence of the template

if (!File.Exists(tmplFile))

{

Debug.LogError("Missing the template file!");

return;

}

// Try to create the new template

try

{

// Read the file to a variable than format it with the new data

var template = File.ReadAllText(tmplFile, System.Text.Encoding.UTF8);

m_TemplateFile = string.Format(template,

m_ClassName,

DevName,

DateTime.Now

);

// Determine the correct output file

var targetFile = Application.dataPath + "/Bengsfort";

switch (type)

{

case ScaffoldDialogType.Component:

targetFile += "/Components/" + m_ClassName + ".cs";

break;

case ScaffoldDialogType.Entity:

targetFile += "/Entities/" + m_ClassName + ".cs";

break;

case ScaffoldDialogType.System:

targetFile += "/Systems/" + m_ClassName + ".cs";

break;

}

// Reformat the path to the output file to be platform agnostic

var newClass = targetFile.Replace('/', Path.DirectorySeparatorChar);

// Write the shiny new file to disk

File.WriteAllText(

newClass,

m_TemplateFile

);

// Tell Unity to import the asset

AssetDatabase.ImportAsset(

newClass.Substring(newClass.IndexOf("Assets" + Path.DirectorySeparatorChar + "Bengsfort")),

ImportAssetOptions.ForceUpdate

);

}

catch (FormatException e)

{

// Oh noes! D: It failed!

Debug.LogError("There was an error creating the new class!");

Debug.LogError(e.Message);

}

}At first, everything worked great... except for it crashing when trying to format the file. I tried debugging the issue for hours, but then I finally found out the issue; which was deceptively simple: Escape the brackets.

As it turns out, every time String.Format sees a {} it assumes that the contents needs to be formatted with some sort of value! Looking back, it was such a 'duh' moment. The solution was to just escape the brackets by adding double brackets, and once I did that the entire thing started working beautifully.

// {0}

// Created by {1} @ {2:d}

using System;

using FlyingIsHard.Assets.Bengsfort.Components.Core;

namespace FlyingIsHard.Assets.Bengsfort.Components

{{

[Serializable]

public class {0} : BaseComponent

{{

}}

}}You can check out the entire editor window class as well as all of my templates in this gist on Github.

So far this setup has worked really well and has increased my productivity a lot. That said, I will likely tweak this in the future to contain an Entity manager so there will only be a single instance of any given System acting on entities based on a component identifier that will determine whether or not the system cares about a specific entity, but I'll leave that for another day.

Stay tuned for more Flying is Hard logs, and maybe follow along on twitter @bengsfort.